An international team of researchers has uncovered how wild ancestors of modern crops hold the key to preserving and restoring the planet’s hidden soil biodiversity. This landmark study is one of the largest of its kind and reveals that crop wild progenitors (CWPs) nurture unique and ecologically vital underground communities of microorganisms, offering valuable insights for sustainable agriculture and climate-resilient ecosystems.

The study, titled “Native edaphoclimatic regions shape soil communities of crop wild progenitors”, was published in ISME Communications, a prestigious journal from Oxford University Press and the official publication of the International Society for Microbial Ecology (ISME), Netherlands.

Led by María José Fernández-Alonso from the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Spain, the international consortium included 25 research groups from 11 countries — Spain, India, Australia, Mexico, the United States, Argentina, China, Germany, Switzerland, Israel, and Chile. From India, Professor Appa Rao Podile and his team — Dr. Ch. Danteswari and Dr. P.V.S.R.N Sarma from the Department of Plant Sciences, University of Hyderabad have made a notable contribution, particularly in field studies involving the wild relatives of the ‘little millet’ crop.

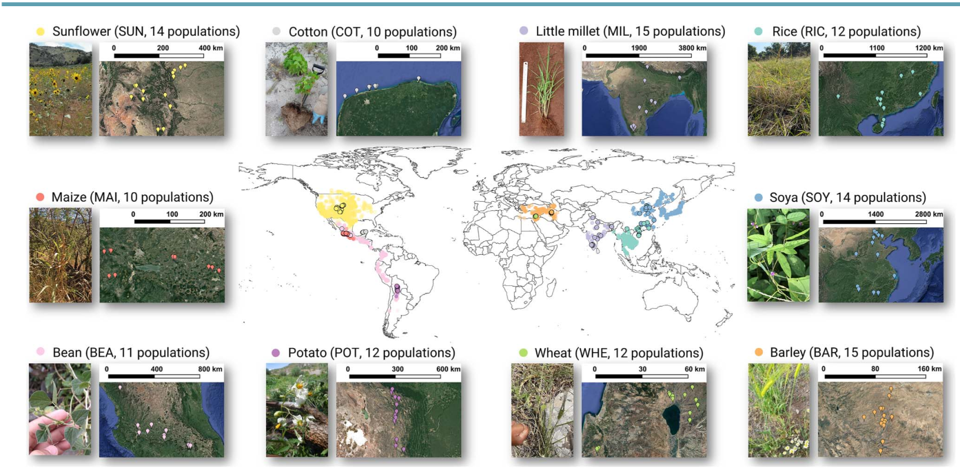

The team of researchers examined 125 populations representing 10 crop wild progenitors collected from their native habitats across diverse environments worldwide. Through detailed analyses of microbial communities in the soil samples, the team discovered that these wild relatives harbor rich and distinct microbial ecosystems including bacteria, fungi, protists, and invertebrates, each finely adapted to their specific environmental conditions.

The study identified four major ecoregions shaped by two fundamental environmental gradients: one linked to soil texture and nutrient availability, and another associated with aridity, pH levels, and soil carbon storage potential. Despite differences across ecosystems from deserts to tropical forests and savannas, the team found a shared “core” soil community among all CWPs, suggesting a deep evolutionary connection between plants and their soil microbiomes.

Interestingly, tropical eco-regions were dominated by acid-loving bacteria and fungal parasites, whereas desert soils supported more decomposer fungi and heterotrophic protists. Each wild crop species also appeared to cultivate its own distinct microhabitat, reinforcing its role as a keystone species in maintaining underground biodiversity.

Professor Appa Rao Podile emphasized the broader implications of the findings: “Understanding the natural microbiomes of wild crops helps us reconnect agriculture with its ecological roots. These findings pave the way for nature-based solutions that can enhance soil fertility and sustainability.”

The research underscores the urgent need to conserve crop wild relatives, not only as genetic resources for plant breeding but also as reservoirs of microbial diversity essential for healthy soils. By linking plant evolution, soil ecology, and environmental adaptation, the study sets a new benchmark for integrating biodiversity conservation with agricultural innovation.

This pioneering global mapping of soil biodiversity associated with crop wild progenitors provides a scientific foundation for restoring degraded soils, developing climate-resilient farming systems, and advancing microbiome-based agricultural technologies there by bringing modern agriculture closer to its natural origins.

Reference:

ISME Communications (2025). Native edaphoclimatic regions shape soil communities of crop wild progenitors. https://doi.org/10.1093/ismeco/ycaf143